Angler Action Foundation’s Dan Cassani Memorial Fund for Marine Fish Research and Conservation awarded to Katie Ribble, a Florida Gulf Coast University graduate student researching the relationship between pinfish, seagrass beds, and Ciguatera.

You will be taken to PayPal page for AAF Award (Mike Readling)

Katie Ribble has always grown up around the water.

“We had a sailboat when I was growing up, and I remember visiting family along the coast in Maine. My first job was at a local aquarium up there,” Katie recalled. “I was always elbow-deep in the touch tank. The positive reaction from people there was always very rewarding to me when I shared my knowledge.”

That experience provided the foundation for a future career in marine and environmental sciences.

While working on her Master’s degree under Dr. Michael Parsons (director of Florida Gulf Coast University’s Coastal Watershed Institute and Vester Field Station), Katie’s efforts have landed her the first-ever Dan Cassani Fishery Research Scholarship from the Angler Action Foundation (AAF), a not-for-profit conservation group based in Florida.

“To kick off this memorial scholarship, we were looking for a student who demonstrates all of the characteristics Katie exhibits,” said Mike Readling, AAF Chairman. “Initiative, leadership, and an intrinsic understanding that the ‘in-the-mud’, down and dirty basic research can be extremely important and rewarding, even though it might not be as glamorous as something like tracking a famous white shark.”

Katie’s work certainly fits that bill. Among other things, she is delving deep into how pinfish feeding behaviors change in relation to factors such as water temperature.

Throughout their lifecycle, pinfish eat a good variety of things, from tiny zooplankton to other fish to shrimp. (Maybe you’ve encountered one or a thousand pinfish as you sought out seatrout, red drum or snook in the grass flats during your fishing career in Florida.) Pinfish are also grazers of grass and algae – and during certain periods of their lifecycle those can make up the bulk of their diet.

Serving as a primary forage species in Florida, pinfish are a critical part of the food web. Understanding more about their diet, and whether environmental factors such as water temperature trigger an increase in feeding activity, will help us better understand how pinfish fit into Florida’s complex marine systems. But Katie’s research goes even further.

Unknown to many, there is a lot more going on with the grass and algae that pinfish are eating.

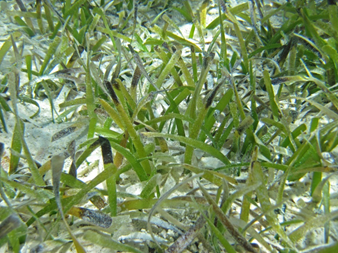

Ever notice that fuzzy, sometimes sort of slimy, coating that adorns the seagrass or algae you are constantly plucking from your jig or lure that is weighted too heavy? Turns out, that slimy stuff has a very interesting and important story.

One of the dinoflagellates (in this case, a marine plankton) that is included in that community of microscopic plants and critters that make up the fuzzy slime is Gambierdiscus spp, which is the only known source of the toxin that causes Ciguatera fish poisoning.

If you’ve never heard of Ciguatera before, you aren’t alone. It is the most frequent seafood poisoning, yet we know relatively little about it. Katie explained that may be because people are unfamiliar with the symptoms and likely source/cause, they may just think they had ordinary food poisoning. Symptoms can include diarrhea, vomiting, numbness, itching, sensitivity to hot and cold, dizziness, and weakness – a list that certainly could be mistaken for any number of maladies.

“It is probably misdiagnosed a lot,” she said. “We’ve associated Gambierdiscus with reef fish in the past, now we are seeing it in other places.”

Which leads us back to pinfish, turtle grass, and the shallow blissful waters of the Florida Keys.

Katie noted that the presence of Gambierdiscus in our waters is nothing new, and this research is not intended to stir up a new scare. In fact, it is a global phenomenon and there are records from the Chinese T’ang Dynasty (618-920 AD). Just last month there was an international conference dedicated to the toxin in France.

If you have heard of Ciguatera, it is probably because you know someone who was diagnosed or maybe visited an area with a tropical reef associated with high concentrations. The point is Ciguatera was only a factor for those who risked eating fish from specific areas.

Barracuda is one of the fish associated with the toxin, as are some groupers, moray eels, and other reef fish.

Barracuda? Remember that time, in between picking fuzzy seagrass blades from your jig, a flash of silver streaked past and just like that your lure or bait was gone – line sliced so cleanly you never even felt a tug? Yep – that was probably a barracuda. Who eat pinfish. Who eat grass coated with yummy brown slime.

Already, Katie’s research has uncovered some interesting tidbits.

While establishing a baseline for her new pet pinfish feeding behaviors, Katie took some turtle grass and a species of Halimeda, a native calcarious green macroalgae from an area in the Keys known to have a particularly strong strain of Gambierdiscus. Part of the first step was to strip the grass and algae clean of all of the fuzzies to see how the pinfish grazed on the clean plants. What Katie found there surprised her.

“It seemed that the fish in my tank would rather starve themselves than eat the clean grass,” she said.

In other words, without the brown slimy stuff as dressing, turtle grass salad is not on the pinfish menu. Katie isn’t sure why that is.

“Maybe they can’t digest the plant without them,” she offered.

As she moves forward, she hopes to uncover other aspects that lead to increased pinfish feeding in the wild. Combined with simultaneous work in Dr. Parson’s lab at FGCU, where he is guiding other students to answer questions such as whether there are normal fluctuations of the Gambierdiscus blooms, and/or whether there are factors that might trigger an unnaturally large bloom. The information might help us understand how the toxin moves up the food chain and across a variety of habitats.

As Katie talked about her early findings, it became easy to see that she settled into the right career path. Her enthusiasm is contagious (Ciguatera is not, by the way), and it is very promising for all of us who are optimistic that we’ll become better stewards of our marine and fresh water habitats. Research like Katie’s points to just how completely all these habitats depend on each other, and that there is a lot of communication between them.

Katie hopes to use her AAF Don Cassani award of $1000 to help pay her way to conferences where she can share her findings.

“Helping these students share their findings is critical,” Readling said. “Putting Katie’s work in front of other scientists is one of the best ways to develop more research ideas. For us fishermen and women, it gives us hope that as a group, we can figure out how to best protect all facets of our environment, from one end of the system to the other.”

AAF encourages you to support the Cassani Scholarship Fund. Any donations made HERE will go directly to the fund and be excluded from all other AAF projects. If you have questions about the program or wish to nominate yourself or another graduate student for the 2019 award, please email Brett Fitzgerald (brett@angleraction.org).

In 2010 a memorial fund was created to commemorate the life and passion of Daniel J. Cassani, with the mission to support and promote marine fish research and conservation. All donations made to AAF in this link will go directly to this fund.

The Angler Action Foundation, based in Florida, is dedicated to conserving our fish, their habitats, and sensible recreational angler access. Angler Action is a 501c3, founded by William Mote. Our primary service project, iAngler, is the first and only database owned by fishermen that contributes directly to state-level stock assessments. Our mission is to continue to help improve fishery research, educate ourselves, other anglers and fishery managers, and continue with best conservation practices.