If you have ever been grouper fishing, I know this has happened to you: You feel the thump of a bite, reel down and next thing you know the fish has “rocked you up” and before you can react, your line goes slack. Fish – and tackle – gone. More times than not the tackle failure takes place at the connections, such as the knot connecting the leader to swivel.

Ecologists have a handle on the basic linkages of such “trophic” connections, and I bet most anglers have an intuitive understanding of this too. But even though we grasp the importance of forage fish like pinfish, there is not a thorough enough understanding of how or why their populations change over time. Drawing back the curtain on the life history dynamics of forage fish is key to help us prevent the types of trophic “break-offs” that could have devastating impacts on our fisheries.

The good news is we’re on our way to gathering this kind of information. Last year the Florida Forage Fish Research Program (FFFRP) – a collaboration between the Florida Forage Fish Coalition, Florida Fish & Wildlife Research Institute (FWRI), and academic institutions –funded two student-led research fellowships and is currently raising funds for additional fellowships in 2018 and beyond. This work will shed some interesting and important light on forage fish populations and their impacts on predators, with the added benefit of supporting the next generation of fisheries scientists.

Eyeing Pinfish Research

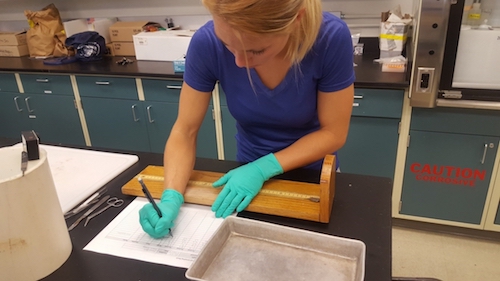

Terry Tomalin, the late Tampa Times outdoors editor, once suggested to a friend that “Gut Content Analysis” would make a great name for a punk band. FWRI’s Fish Biology “Gut Lab” rocks at identifying partially digested forage items found in the stomachs of the predator species we target. For example, a 2006 study conducted by the Florida Wildlife Research Institute (FWRI) showed that forage fish account for 40% of a snook’s diet in the Charlotte Harbor Estuary, and pinfish make up half of that (20% overall). I know gator seatrout love 'em - it was a pinfish that landed my biggest to date (see above right).

But when it comes to where these critically important pinfish spawn and spend their lives, we have a lot to learn. We’re left to wonder whether pinfish offshore spawning that supplies the Eastern Gulf’s estuaries occurs in a few critical locations or whether spawning activities are spread out. We also don’t know whether pinfish from all of the Gulf estuaries move offshore to spawn at once, or whether they take turns. Fortunately, scientists from the University of South Florida (USF) plan to change that.

USF researchers awarded the first of two FFFRP fellowships in 2017 will use a new technique to discover the secret lives of pinfish. Such insight is gained not by following these fish around and watching what they eat, but rather by examining chemical markers stored in the fish’s tissues. By analyzing carbon and nitrogen isotopes stored in the core of pinfish eye lenses, USF scientists will gain insights about where they were spawned and spent the planktonic phase of their lives before settling into our coastal estuaries.

Foraging Arena Theory

We all know that habitat loss and fragmentation can reduce recruitment of juveniles into gamefish populations. But couldn’t limitations on prey availability also reduce recruitment of wildly popular species such as redfish?

For many years, FWRI collected data on forage abundance in Gulf estuaries. Now, the FFFRP fellowship program is funding a University of Florida researcher to evaluate trends for what they think are the ten most important forage sources for redfish and gag grouper. They will specifically try to identify any significant population changes in these key forage species, and determine what effect, if any, these fluctuations might have had on redfish and gag grouper populations. After all, we can’t adequately protect healthy populations of iconic species such as redfish and gag grouper, unless we understand such basic predator-prey relationships.

These promising fellowships will publish their results this year. In the meantime, the Florida Forage Fish Coalition is hopeful that the FFFRP can secure funding for many more fellowship projects in the future. This work will provide valuable scientific insight to the FWC as they work to maintain healthy forage, predator populations, and fisheries as outlined in the Florida Forage Fish Resolution passed in June 2015.

Visit www.floridaforagefish.org to take the Florida Forage Fish Coalition pledge. You can donate to the Florida Forage Fish Research Program at https://www.igfa.org/fffrp.

Editor's Note: The Florida Forage Fish Coalition is a small yet diverse coalition of organizations who understand the critical importance of the baitfish that swim in Florida waters. Some coalition members contributed to information in this story. Please do take the time to visit the web page and take the pledge!

Image credits: Pinfsih in Hand image courtesy of Live Advantage Bait. Silhouette pinfish image courtesy of NOAA. Lab gut analysis image courtesy Meaghan Faletti. Redfish in hand image courtesy of Tim Boothe. Lunker Trout image courtesy Ava Fitzgerald.